Sunday was Father’s Day. On Monday I cut myself shaving. Again. These two things are related but I won’t say exactly how just yet. First, there are a few items that I need to get off my chest.

To start I’ll admit there’s a lot I don’t know about my father. There are many gaps in his history about which I never had the chance to inquire. But one thing I do know, the one thing that’s apparent from all the second hand tellings of his life, is that he was a very disciplined and focused person. In that way, I’ve always wished that I was more like him.

As a Montana teenager he held down multiple jobs, managed straight A’s, and spent what spare moments he had left either riding his horse or reading a book. He never had any girlfriends in high school. I can relate.

When applying to law school my dad wrote just four words on his application essay: “I love the law.” That’s it.

The man was also arrogant, as it turns out. But it worked. Later that year he moved to California to attend Hastings.

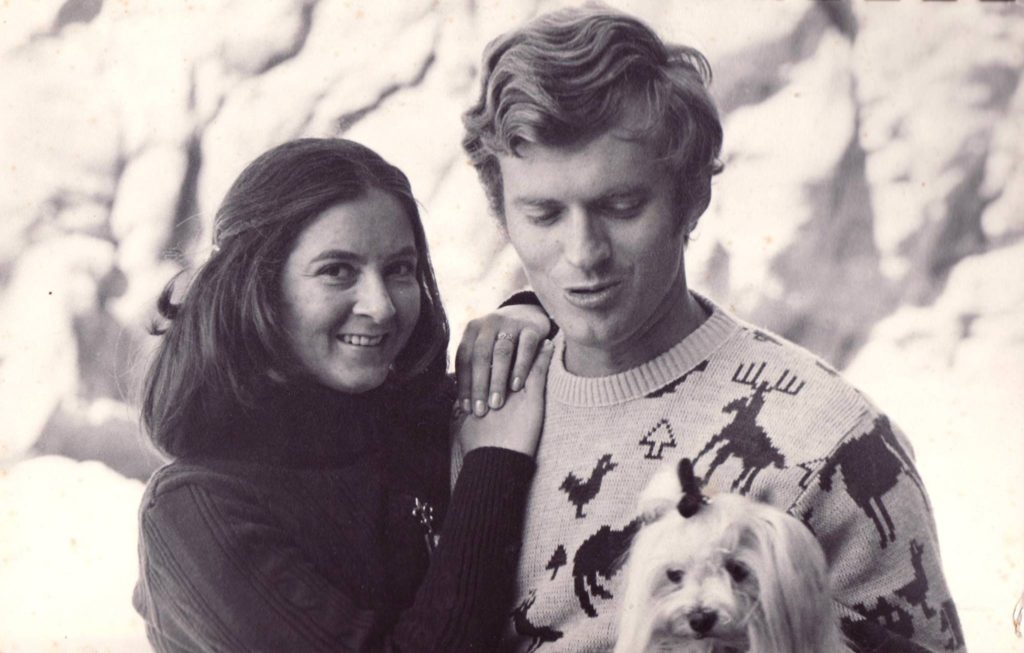

On campus he met a dark haired debate champion with ballerina legs and a razor blade intellect. He obsessed and pursued. She wanted no part of him, but he persisted. Years later they were married on the steps of San Francisco City Hall. They shared a hotdog to celebrate.

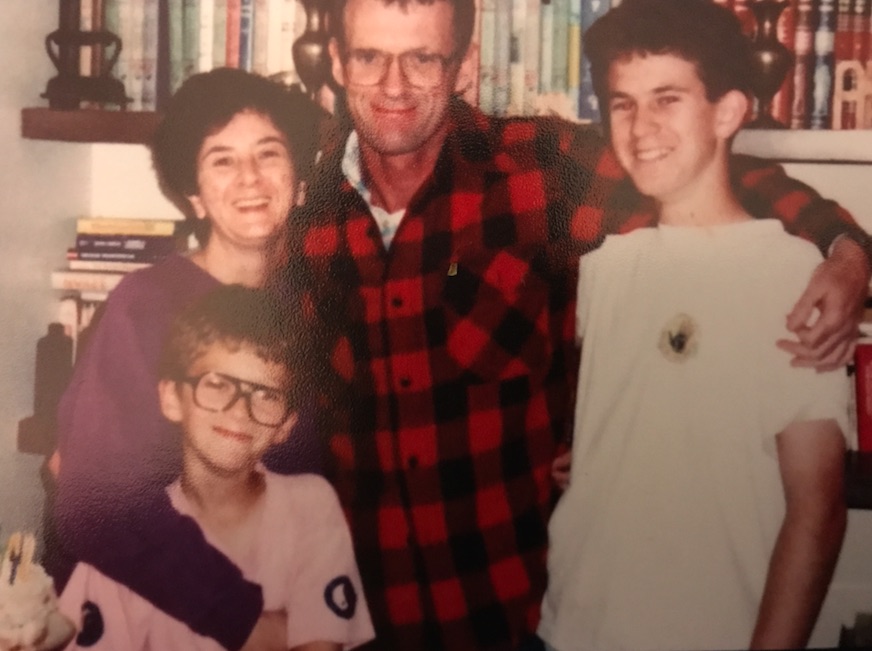

My parents moved from the Bay Area to Orange County in the 1970s. They built a successful law practice. They had two boys and lived less than two miles from the beach. It was an idyllic existence.

During the 1980s my dad went through a series of medical procedures. He had a cancerous skin lesion removed from his lip. He underwent surgery after injuring his back in a swimming accident. Both operations called for blood transfusions. One of those transfusions changed my father’s life forever.

Times were different then. Blood banks weren’t as careful. Awful diseases came with stigmas that were just as bad. Many of them still do. Not that my brother or I knew anything about that.

I don’t blame my parents for concealing my dad’s HIV. It was 1987. They had a business to run, and an upstanding image to protect. More importantly, they wanted their children to exist in eden for as long as was conceivably possible. Back then AIDS was a death sentence, even for the well-to-do. Why burden the kids?

But in March of 1991 the glass cocoon they had so carefully built shattered into a million pieces. One of the medications my dad took caused an unfortunate reaction. His pancreas ruptured. Enzymes spilled through his insides like toxic waste. I’ll never forget him staggering on the steps of our kitchen stairs. He was rushed to the emergency room.

My mother faced a gut-wrenching decision. Her husband’s body was shutting down, organ by organ, and the only way to fend off the inevitable was to induce a coma. Do it, however, and he might never wake up. But the alternative? I guess it wasn’t really a choice.

Before he went under my dad glanced at my mom from the gurney. The chemicals were already coursing through his body as he spoke out, “How about a hot meal and a good dessert?” Pain killers had dulled his senses, but not his sense of humor, apparently. But was he really laughing in the face of death? Or was it simply a drug-induced delusion. We’d never know.

In a matter of moments the lights went out. Consciousness faded into the background. My father turned from flesh and blood human being into an overrepresented head of broccoli. It was like this for weeks.

I do not often like to dwell on the occasions when we went to visit him while he was this state of limbo. But when I do it’s as if I am transported. In so many ways I am still there…

Pale sunlight casts a yellow hue over the eggshell walls. The air conditioning vent hums an ominous, unrelenting tune while a tower of medical equipment groans and sighs. The collection of tubes and wires and buttons keeps the beat, and my dad, alive. But the pace is grim. The whole room reeks of antiseptics. They might as well just draw a chalk line around the body.

Mom encourages my brother and I to talk to our father. We are the carrots meant to keep the steed trotting forward. We tell him about the things we want him to wake for. To see us graduate from college and get married. To hug his future grandkids. I notice what looks like a tear forming in the corner of his eye. It has to be a sign, right? Everything is a sign.

As we speak my mother clutches a gray tape player like an old woman clinging to her Sunday bible. She will use it record messages from her boys, ones that can be played even in their absence. Even after visiting hours have come and gone and the rest of the world drifts into silence. She hopes the power of these recordings might make the difference in bringing her husband back from the darkest of nights. It’s all she can do. It wont be enough…

My dad spent his 44th birthday at the Mission Hospital in Laguna Beach. One week later he was dead. I was 10 years old. My brother was 15.

The times that followed were not my favorite. I was affected. I know that now, even as much I denied it as I was going through it. I wanted to pretend that I was strong enough on my own, that I didn’t have to use his absence as a crutch just because I “missed out” on certain experiences. I, like every young person before or since, was a fool.

I did miss out.

I missed him teaching me how to drive a stick shift.

I missed him reading anything of consequence I ever wrote.

I missed introducing him to my bride-to-be.

I missed him taking me on more adventures to the San Diego Zoo and the Star of India. Climbing aboard the old sail boat was like stepping into one of the pirate tales he used to improvise at bedtime. Captain Bob raiding the port of Tortuga with a rowdy mob of drunken scoundrels. Those stories were the best.

More than all that though, I really just missed the chance to get to know who my dad was as a human being. What a marvelous investigation it could have been.

I wonder, more often as years go by, what my father would make of this incredible, astounding, terrifying, connected world we live in today. What would he do with the internet? Would he lament the loss of privacy and attention spans? Would we have deep conversations that lingered on until 3 a.m?

Would he have taught me how to shave?

I have, you must understand, one of those faces where the hairs grow in swirly thickets of barbed wire roses. There is no sanity to my whiskers, no grain to go with or against. There is no shower hot enough to soften the bristly weeds that spring from my neck, and no overpriced miracle cream or ceremonial oil that can deliver salvation. There is only blood, a symptom of the nicks and cuts that hound me for days on end. And you know who I blame? I blame dad. I blame his Irish DNA and all the baggage it drags along with it. I blame the fact that he was never around to tell me how to make things work.

I have this suspicion that buried in that big brain of his was a secret technique, perhaps based on an old wive’s tale or an obscure proverb, that could ameliorate my ritualistic self-mutilation. His skin was like my skin, after-all. His wisdom could’ve been my wisdom. And this wisdom, passed down from the generations, would liberate me, both from the dread of anticipation and the pain of experience. But the fantasy is only as real as leprechauns that hold pots of gold at the end of rainbows.

The older I get the more I realize there are no secrets to shaving, or life. Just good days and bad days.

On good days the hairs wave white flags. The blades glide. There is no residual burn, and no need to tear up little squares of tissue paper to patch up the tiny wounds. Everything just happens.

But even on bad days, I should try to remember that things really aren’t so bleak. Perhaps I just need to give myself permission to bleed every once in awhile. Perhaps I just need to laugh at the absurdity of it all. I think that might be the philosophy that got my dad through the hard times. And if that’s true, then it’s good enough for me too.

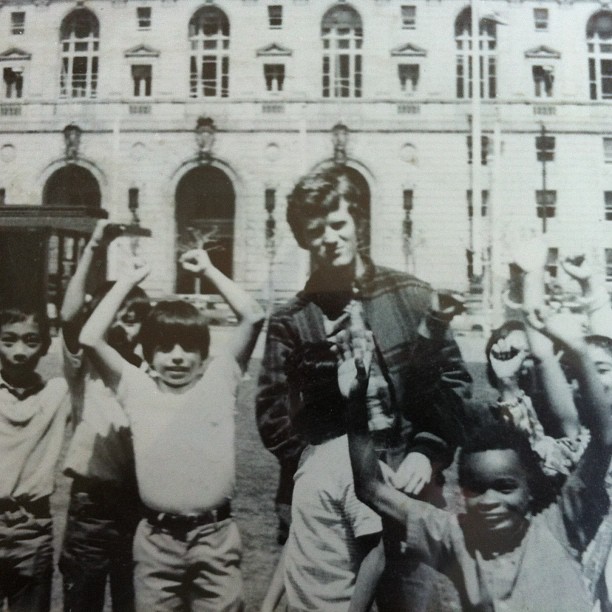

Top photo: Me holding a picture of my dad, Allen Jr. (age 11) with his dad, Allen Sr. (the Colonel) circa 1958

You are an amazing writer Brian and you captured what you do know of your father very well. He would be proud, and you are probably more alike, especially in your sharp thought processes and wit, than we will sadly ever know. I wish I could’ve met him, or him my children. But I appreciate and cherish the stories of him, and keeping his memory alive and known with our future generations. Let’s keep it going.

Thank you for rawly and authentically sharing the essence of your understanding and experience of your dad. Those jigsaw whiskers are your dad’s regular visits with you! Sending love and aloha.